James Isiche

You put your life on the line. The people who come to poach elephants...come with sophisticated weapons. You have to be alert. All the time. But if you take it like a calling, it’s very rewarding.

Why African countries should ratify the High Seas Treaty

When Malawi ratified the High Seas Treaty on 27 February, it became the 18th country to do so. But Malawi led the way by being the first, and still only, landlocked country in the world to ratify it. By doing so, they show that all countries benefit from a healthy ocean—not just those with expansive coastlines or large naval forces.

The high seas are the ocean areas that lie outside any country’s jurisdiction. Covering two-thirds of the world’s ocean, they contain vital marine ecosystems that are often overexploited because of huge gaps in current legislation.

From fishing to shipping to underwater mining, wealthy nations have dominated and reaped the benefits of the high seas for centuries, while countries with limited marine resources have largely been left with the consequences of environmental destruction not far from their borders.

The High Seas Treaty would regulate human activities in these areas, not only conserving precious ecosystems but also ensuring every nation—even landlocked ones—can benefit from them. The treaty’s preamble makes this goal clear, recognising that it should contribute to ‘a just and equitable international economic order which takes into account the interests and needs of humankind as a whole and, in particular, the special interests and needs of developing States, whether coastal or landlocked.’

For the treaty to enter into force, 60 countries must ratify it. So far, 21 have ratified. Of those, only three are African: Malawi, Mauritius, and Seychelles. We urgently need more to step forward.

The UN’s African Group was instrumental in negotiating the treaty before it was opened for signature. Considering the African Group has 54 Member States, they have the power to take the process over the last hurdle. Doing so before the UN Ocean Conference this June is crucial for meeting the global goal of conserving 30% of the Earth by 2030.

By enshrining this treaty into law, African countries can not only help protect a vital shared resource that benefits people and animals everywhere, but they can also step up their own scientific research while expanding the continent’s influence in how this resource is managed. What’s more, they can use the treaty’s provisions to support their individual goals under the SDGs, Agenda 2063, and national development plans.

Here are some of the ways the High Seas Treaty can promote economic development, scientific advancement, food security, and human health across the continent.

Economic activities that sustainably use oceans, seas, lakes, rivers, and other waterways generated nearly US$300 billion in Africa in 2018 and created 49 million jobs. Many African nations are developing their own Blue Economy strategies, whether they are Small Island Developing States (SIDS) like Seychelles, Mauritius, Cabo Verde, and Comoros; larger countries with well-developed coastal economies like South Africa, Kenya, and Egypt; or landlocked countries like Ethiopia.

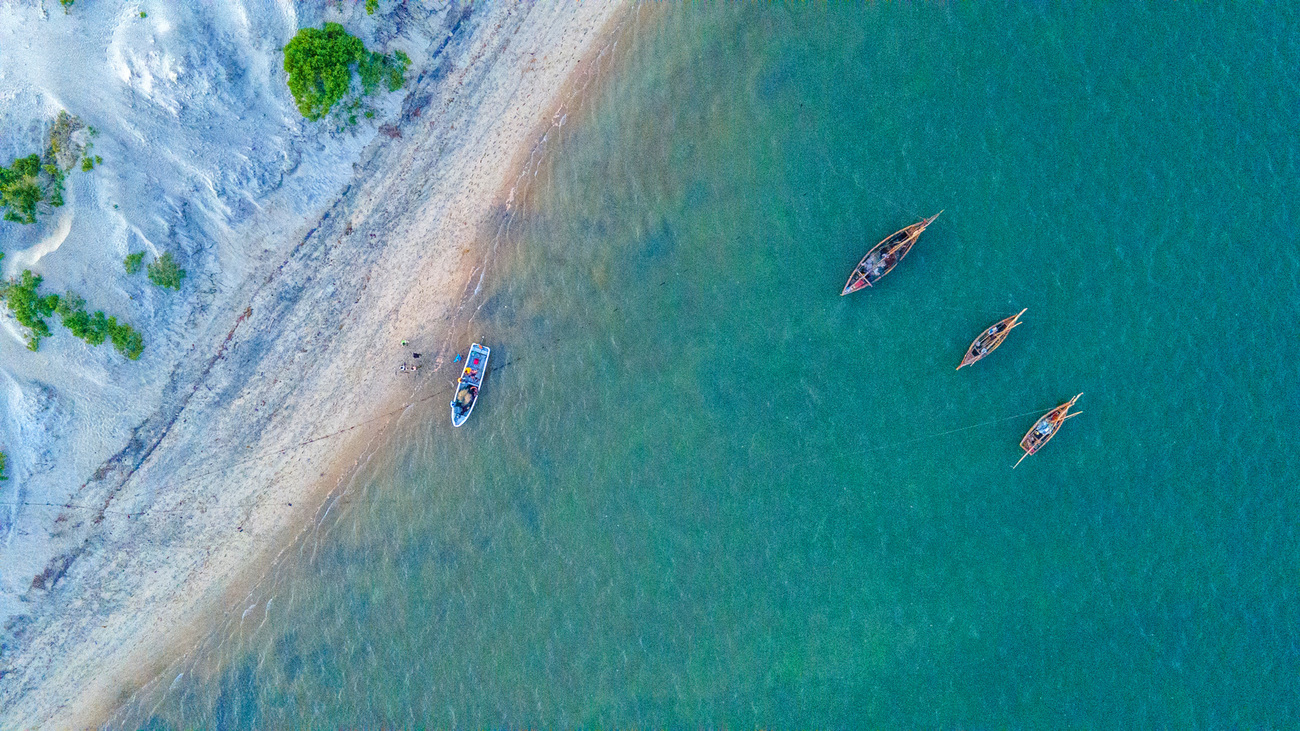

Sustainable fisheries are a key industry for most of these strategies. Right now, many of these countries, such as Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Madagascar, and Mozambique, find that foreign fishing fleets are trawling the international waters just beyond—and sometimes just within—their own national waters, or Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). This is called ‘fishing the line’, and it depletes the stocks that local fishers depend on.

For example, Mozambique is one of the lowest-income countries in the world, with a GDP per capita of only $1,217 in 2016. Portugal and Japan spent more than 400 hours within 20 nautical miles of Mozambique’s EEZ, and Spain spent more than 800 hours.

The treaty enables the establishment of marine protected areas where human activity is strictly regulated or even prohibited. Currently, only 1% of the high seas are highly or fully protected, compared to 17% of land. Protecting these precious ecosystems would give fishing stocks time to recover and would ensure their habitats can support new generations of marine life. With better regulated, sustainable fishing practiced on the high seas, coastal countries could strengthen their livelihoods.

When the African Group was negotiating the High Seas Treaty, they focused particularly on the fair and equitable use of marine genetic resources, the genetic materials found in any marine organism, ensuring that even landlocked Parties to the treaty, like Malawi, can benefit.

Marine genetic resources could also be monumental for advancing scientific capacity across the continent.

If their country is a Party to the High Seas Treaty, African scientists can expand their research, access data and resources, cultivate partnerships with researchers around the world, and expand the role of African scientists and researchers not just in academia but also in decision-making.

The treaty lays out mechanisms for resource sharing and transfer of marine technology, so researchers in any country can access equipment, expertise, software, and data.

In 11 African countries, fish protein makes up more than 50% of people's protein intake from animals. For countries like Cape Verde, Sierra Leone, Equatorial Guinea, and Ghana, the health and abundance of marine fish is tied to the health and food security of people.

The High Seas Treaty will help protect fish stocks by creating marine protected areas and by setting standards for environmental impact assessments, which look at the potential impacts of activities like shipping and mining on biodiversity and the ecosystem.

But the high seas are also important for food security beyond providing fish. The ocean's health influences climate patterns, directly impacting rainfall, temperature, and extreme weather events like droughts and floods. These factors greatly affect agricultural productivity, a cornerstone of food security for the entire continent, including landlocked nations like Malawi and Zambia, where IFAW has worked to promote sustainable, climate-smart farming practices.

One of the treaty’s guiding principles is that the high seas are a ‘common heritage of humankind.’ Representing the African Group during the treaty negotiations, Algeria’s ambassador said adopting the treaty without including this principle ‘would be like giving life to a treaty of this importance without a soul, or like putting a ship in the water without a navigational instrument.’

After being so crucial to the treaty’s negotiations, African countries now urgently need to step up with ratification. This is our chance to right the balance of scientific and economic disparity that has long plagued the continent—all while safeguarding a vital global resource for future generations.

We can’t squander it.

James Isiche

You put your life on the line. The people who come to poach elephants...come with sophisticated weapons. You have to be alert. All the time. But if you take it like a calling, it’s very rewarding.

Our work can’t get done without you. Please give what you can to help animals thrive.

Unfortunately, the browser you use is outdated and does not allow you to display the site correctly. Please install any of the modern browsers, for example:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari