Shark information & FAQs: everything you need to know

Shark information & FAQs: everything you need to know

Sharks continue to be some of the most misunderstood members of the animal kingdom. People fear them, and fishermen are applauded for killing them, despite sharks only being responsible for seven human deaths in 2024. For comparison, bees, elephants, and crocodiles are responsible for far more deaths.

Summer 2025 marks the 50th anniversary of the movie Jaws, in which a great white shark terrorises a seaside town. The film, directed by Steven Spielberg, has been blamed for spreading false information about sharks, increasing trophy hunting in the US, and damaging shark conservation efforts. Spielberg himself acknowledges this impact and has publicly said that he ‘truly regrets’ the decimation of shark populations following the film’s success.

At IFAW, we’re committed to protecting sharks and the oceans they live in. We’re global leaders in marine conservation and advocate for higher protections and trade limits for shark species under international agreements like CITES.

In this blog, we debunk the myths and answer some of the most frequently asked questions about sharks. Read on to find out where they live, how many teeth they have, how often shark attacks occur, and more.

Did you know that whale sharks have more teeth than great whites? Or that humans kill far more sharks than sharks kill humans? Read on to discover more important information about sharks.

Are sharks fish or mammals?

There’s a lot of confusing information about sharks out there, so let’s set the record straight. Sharks are fish, not mammals. Sometimes, sharks are mistaken for mammals because they share certain physical traits with dolphins and whales. But like other fish, sharks are cold-blooded, breathe through gills instead of lungs, and have bodies covered in denticles (tooth-like scales). Sharks are also missing several key mammalian traits—they don’t grow hair, produce milk, or have a neocortex (the part of the brain involved in perception and thought, among other things).

Sharks are members of the group Selachimorpha, which is within the group Neoselachii. In Neoselachii, alongside sharks, are rays, skates, and sawfish. These are sharks' closest relatives.

Marine mammals, on the other hand, are more closely related to hippos, giraffes, buffalo, and deer than they are to sharks. They evolved millions of years ago from land mammals.

Where do sharks live?

Sharks can be found off the coasts of every continent in the world. Some stick to shallow, coastal waters, while others prefer deeper waters in the middle of the ocean.

Great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias, listed as vulnerable in 2025) are found all around the world, with large populations in South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, the North Atlantic, and the Northeastern Pacific.

Hammerhead sharks (Sphyrnidae family, ranging from critically endangered to vulnerable in 2025) can be found in tropical and subtropical waters around the world, with a preference for coastlines and continental shelves. They are most often seen around the Galapagos Islands and the Great Barrier Reef.

Bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas, classed as vulnerable in 2025) are found in shallow coastal waters around the world. They can tolerate both freshwater and saltwater habitats, so they are sometimes found venturing into rivers.

How many types of sharks are there?

There are more than 500 species of sharks swimming in the ocean today. They are split across eight orders:

- Carcharhiniformes

These are the ground sharks, the largest group of sharks. This order includes tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier, near threatened in 2025), great hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna mokarran, critically endangered in 2025), and blue sharks (Prionace glauca, near threatened in 2025).

- Hederodotiformes

This order only contains one living genus, the bullhead sharks. The genus includes the Japanese bullhead shark (Heterodontus japonicas, least concern in 2025) and the Galápagos bullhead shark (Heterodontus quoyi, least concern in 2025).

- Hexanchiformes

There are only seven living members of this order, which includes frilled sharks (Chlamydoselachus anguineus, least concern in 2025) and broadnose sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus, vulnerable in 2025).

- Lamniformes

These are the mackerel sharks, which include some of the most well-known shark species. In this order are basking sharks (Cetorhinus maximus, endangered in 2025), great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias, vulnerable in 2025), shortfin mako sharks (Isurus oxyrinchus, endangered in 2025), and goblin sharks (Mitsukurina owstoni, least concern in 2025).

- Orectolobiformes

This order is commonly known as the carpet sharks, so named because they feed on the seabed, picking up small prey like molluscs and crustaceans. Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus, endangered in 2025) are one member of this order.

- Pristiophoriformes

These are the saw sharks, which are known for their long, pointed snouts lined with sharp teeth, resembling a saw.

- Squaliformes

This order contains gulper sharks (Centrophorus granulosus, endangered in 2025), kitefin sharks (Dalatias licha, vulnerable in 2025), bramble sharks (Echinorhinus brucus, endangered in 2025), the angular roughshark (Oxynotus centrina, endangered in 2025), and the Pacific sleeper shark (Somniosus pacificus, near threatened in 2025).

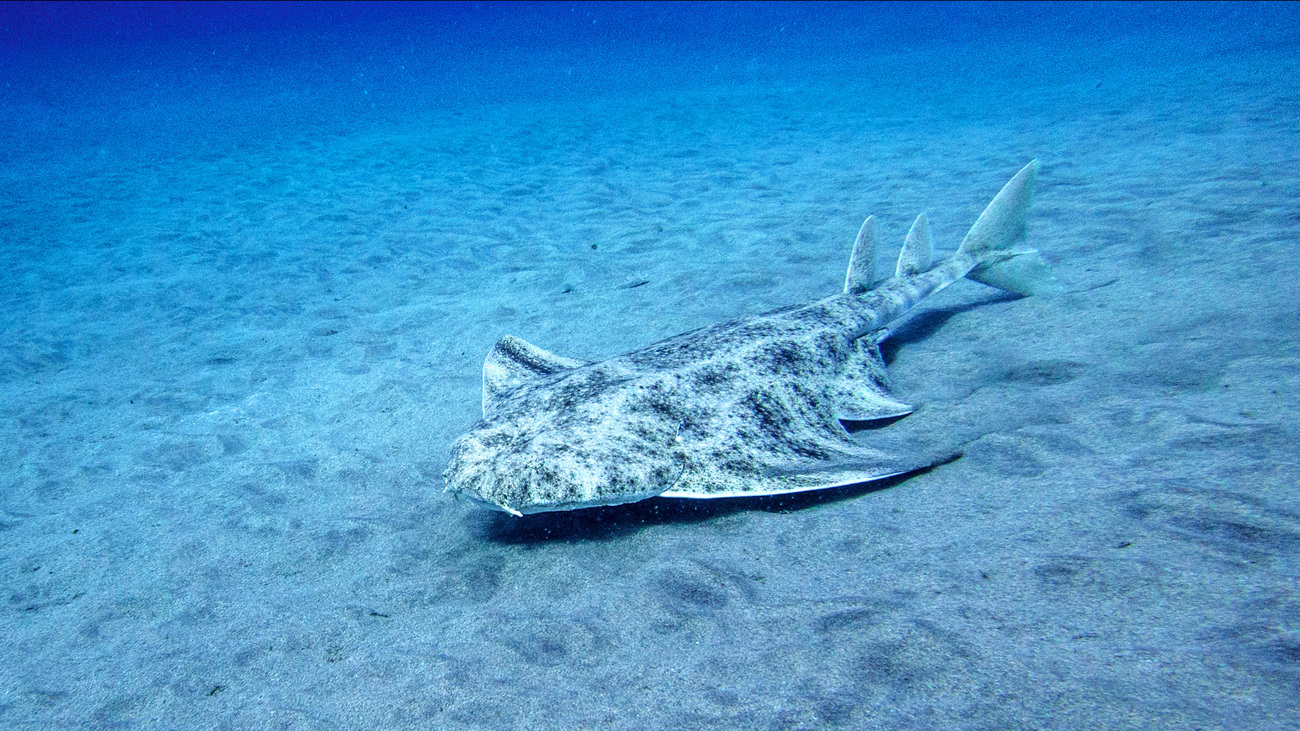

- Squatiniformes

This order contains only one living genus, the angelsharks (Squatina squatina, critically endangered in 2025).

What do sharks eat?

Almost all sharks are carnivores that feed on other animals. Most sharks have molluscs, fish, and crustaceans on the menu, and they typically swallow their food whole. Larger shark species consume bigger fish and marine mammals like dolphins and sea lions, which they don’t swallow whole but eat in bites using their sharp teeth. Filter feeders, such as whale sharks, gulp large mouthfuls of water and sift out plankton, shrimp, and small fish using modified gills.

How many teeth do sharks have?

There’s a huge range in the number of teeth sharks have. Whale sharks hold the record for the sharks with the most teeth—their mouths are brimming with 3,000 tiny, sharp teeth. Great white sharks, known for their fearsome bite, only have around 300 teeth. Sharks continuously shed and replace their teeth throughout their lives.

Do sharks have bones?

Sharks do not have bones. Instead, they have a skeleton made of soft cartilage. Because cartilage is more flexible and lighter than bone, it helps sharks manoeuvre in the water and minimises the energy they need to expend while swimming.

How fast do sharks swim?

The speed a shark can swim depends on its species. Most sharks cruise around the ocean at a leisurely pace.

Some sharks are particularly slow. The Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus, vulnerable in 2025) moves at just 2.9 kilometres per hour (1.8 miles per hour).

The fastest known shark species is the shortfin mako shark. It has been clocked swimming at a whopping 74 kilometers per hour (45 miles per hour) in short bursts. Great white sharks are also fast, capable of swimming up to 50 kilometres per hour (35 miles per hour).

How long do sharks live?

Most sharks live for 20 to 30 years in the wild, but some species can live far longer lives. At the extreme end of the longevity scale are Greenland sharks, which can live for at least 250 years, making them the longest-living vertebrates (backboned animals) in existence. To learn more about Greenland sharks and other animals with lengthy lives, check out our blog on the animals with the longest lifespans in the world.

How do sharks sleep?

Sharks don’t sleep in the same way humans do, but they do have periods of activity and rest. Until very recently, it was assumed that sharks never sleep because they have to constantly swim to pass water over their gills and extract oxygen. But not all shark species use this method of breathing.

Instead, some use the muscles in their mouths to pump water over their gills, which allows them to breathe even when they’re resting. Research from 2022 uncovered that New Zealand’s draughtboard sharks (Cephaloscyllium laticeps, least concern in 2025)—a mouth-breathing species—do in fact fall asleep during their resting periods, sometimes with their eyes open!

How do sharks mate and reproduce?

Unlike some fish, sharks are internal fertilisers, meaning the egg and sperm come together inside the female shark’s body. Some sharks lay their fertilised eggs on the ocean floor, and others give birth to live young (called pups).

Though sexual reproduction is the most common method among sharks, some species are capable of a process of asexual reproduction known as parthenogenesis, which is uncommon among complex vertebrates. One species with this ability is the zebra shark (Stegostoma tigrinum, endangered in 2025).

How many sharks are killed each year?

Humans kill an estimated 100 million sharks every year. That’s an average of almost 274,000 sharks every day, over 11,000 sharks every hour, and around three sharks every second.

One way people kill sharks is through shark finning. This involves catching sharks, removing their fins, and discarding them back into the ocean, where they often die slow, painful deaths. Shark fins are in demand due to their monetary and cultural value. An estimated 73 million sharks are killed for their fins each year.

Bycatch is another way sharks are killed by humans. This is the unintentional catching of sharks in fishing nets.

Sharks are also hunted for their meat, internal organs, and skin to make food, leather, and other products. However, shark meat carries toxic amounts of substances like mercury and ciguatoxin, so it poses a risk to people who eat it.

How many people do sharks kill each year?

In contrast to the staggering number of human-induced shark deaths, fewer than 10 people worldwide are killed each year by shark attacks. For comparison, every year, about 24 people die after being hit by flying champagne corks, about 700 people die from toasters, and about 24,000 people are struck and killed by lightning.

Experts believe shark attacks on humans are usually unintentional. They are most likely cases of confused sharks mistaking kicking feet for small fish.

What threats do sharks face?

More than one-third of shark species are threatened with extinction as of 2025. Populations of sharks in the open ocean declined by 71% between 1970 and 2020.

Much of these declines are due to global demand for shark meat and fins, which is pushing some shark species to the brink of extinction. Commercial fishing also impacts sharks through bycatch, when they are accidentally caught in fishing nets.

Meanwhile, sharks are also rapidly losing their homes. Shark habitats—particularly in coastal waters—are being destroyed by residential and commercial development, including through the cutting down of mangrove forests and pollution.

Sharks are particularly vulnerable to all these threats because they take a long time to reach sexual maturity, and most sharks only have a few pups at a time. Many sharks get killed before they have a chance to reproduce, making it difficult for their populations to rebound.

How do sharks help their ecosystems?

As the relationships between species are interconnected, every animal is a critical part of its ecosystem—sharks included. Sharks help keep the ocean healthy and even play a role in mitigating climate change.

Because many sharks are apex predators, they are important for regulating the populations of animals lower on the food chain. When sharks are overfished, this can have ripple effects on the entire ocean ecosystem. If the larger fish sharks eat become overpopulated, they consume too many of the smaller, algae-eating animals, leading to an overabundance of algae. In turn, algae overpopulate coral reefs and kill these crucial marine habitats.

Sitting at the top of the food chain, sharks help ensure biodiversity in the ocean, which is a critical piece of making our planet more resilient to the effects of climate change. This is why protecting sharks is so important.

What is IFAW doing to help sharks?

IFAW works to reduce the number of sharks killed and protect them from overfishing by advocating for limits on the trade and catch that drives shark population declines.

For over a decade, we have partnered with member countries of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) to achieve limitations on the trade of shark species. We have successfully achieved Appendix II protections for nearly 100 species of sharks, ensuring that any continued trade is legally and sustainably managed.

Trade in species listed in Appendix II of CITES is regulated and monitored by governments around the world to ensure it is sustainable. Effective enforcement of CITES shark listings helps prevent illegal trade in shark products and drives better fisheries management.

In addition to advocating for sharks, IFAW provides support to those fighting on the frontlines against wildlife crime, including trainings on enforcing shark protections and identifying shark products in trade. We also help develop technical tools for governments looking to implement CITES protections.

We hope that protection for sharks under CITES will ultimately prevent the trade in shark products from driving these animals to extinction. Learn more about how you can help us take action for animals.

Related content

Our work can’t get done without you. Please give what you can to help animals thrive.