Saving the North Atlantic right whale - North America

Don't fail our whaleresearchers track North Atlantic right whales with specialised equipment

researchers track North Atlantic right whales with specialised equipment

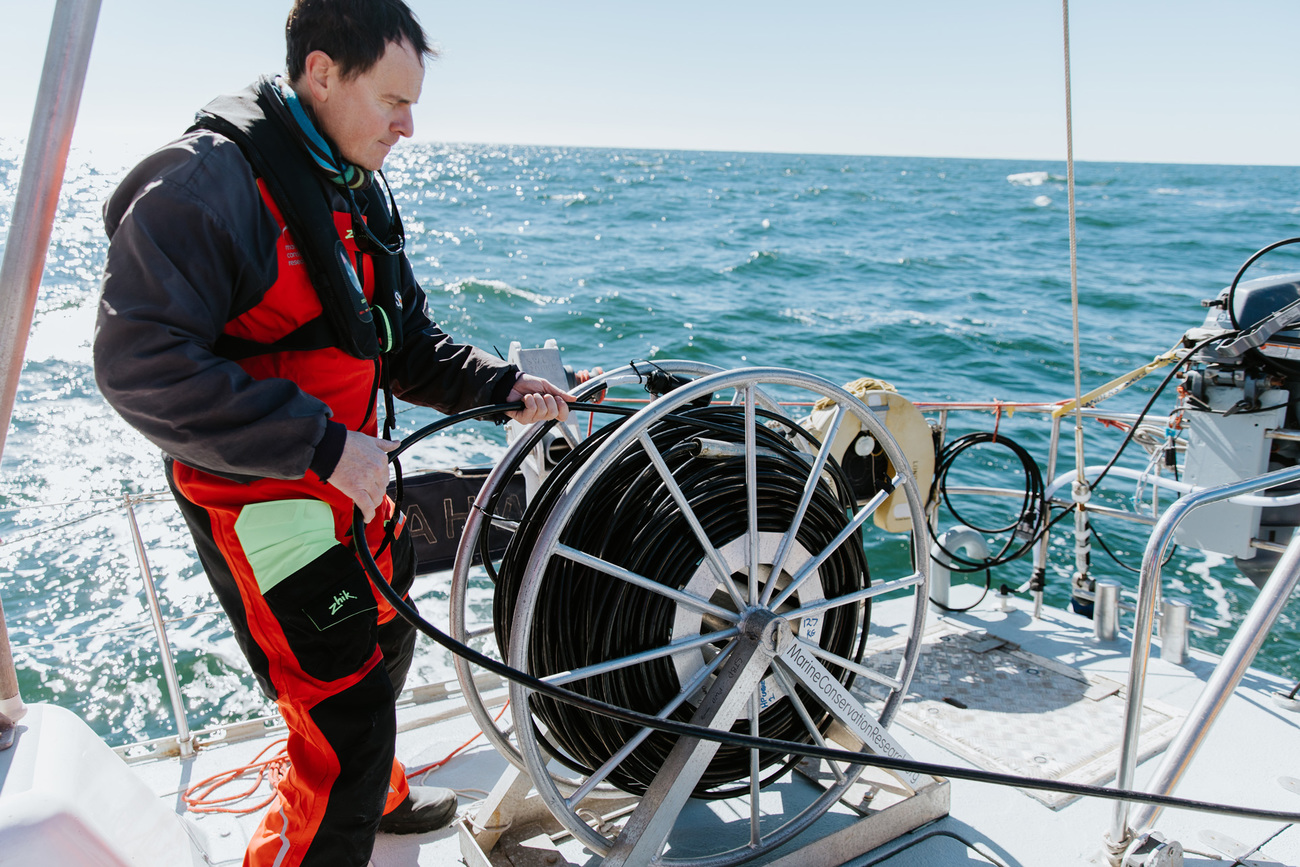

Off the coast of Florida’s Fernandina Beach, Dr. Oliver Boisseau and his colleagues prepare to unspool a long cable out into the ocean. Trailing at the end are three oil-filled tubes containing hydrophones—highly sensitive microphones designed to capture underwater sounds. They’re listening for critically endangered North Atlantic right whales.

Boisseau is the chief scientist aboard the Song of the Whale, a research vessel now sailing a months-long mission up the northeastern coast of the United States. One of the team’s goals is to locate and count right whale mothers and their calves.

That’s no simple task. North Atlantic right whales, though massive, are very hard to find. They spend most of their time submerged, rarely breaking the water’s surface. There are also fewer than 340 individuals remaining on Earth today.

Sadly, humans usually only see them after the whales have been killed by entanglements in outmoded fishing gear or hit by fast-moving vessels.

Although human actions are pushing these whales to extinction, human actions can also protect and conserve them. But it’s difficult to know which changes to make if their exact migration patterns and preferred locations remain a mystery.

The best shot scientists have at finding these elusive whales is by hearing the calls, clicks, moans, groans, and songs they emit through the water.

listening for right whales

That’s why Song of the Whale has advanced audio equipment capable of eavesdropping on large sea mammals. “Right whales and the other baleen whales—the whales that don't have teeth—often produce vocalisations that are very low frequency and sometimes even below human hearing,” explains Boisseau.

In the ship’s research cabin, a buzzer goes off at 15-minute intervals, reminding the scientists aboard to listen in. “It's good to listen at least several times an hour just to check everything's okay with the hydrophones,” Boisseau says.

As the hydrophones trail behind the vessel, they pick up underwater noise and transmit it to onboard computers running software that can decipher it from background noise. If a whale makes a call in the vessel’s vicinity, those monitors will display the frequencies of that call as a series of peaks and valleys on a graph known as a spectrogram, which Boisseau can analyze while he listens through headphones.

The computer’s algorithm is so sophisticated that it can pick out the signatures of different types of North Atlantic right whale calls, such as the “upcall”—which sounds like a short chirp or “whoop”—and assign them scores between 0 and 12 based on their similarity to known calls made by the species.

“We can hear this with our own ears,” says Boisseau, “but it’s always useful to have an independent verification, which is what the computer system is giving us here.”

Spectrogram and audio of two North Atlantic right whale upcalls.

noninvasive research

Key to this technique is that the research vessel itself must not introduce significant background noise that could obscure the sounds made by whales. According to skipper Richard McLanaghan, Director of Marine Conservation Research International, who has led the Song of the Whale program for 30 years: “If you are using hydrophones trailed behind the boat, it's very important that the platform you're working from is as quiet as possible.”

Fortunately, Song of the Whale is among the most noiseless research vessels to glide through the water, thanks to its specially designed five-bladed propeller—not normally used on a sailing vessel—and extra sound- and vibration-deadening materials and mounts for the engine and motors. The custom-designed vessel reflects the efforts of a large team of naval architects, boat-building specialists, fabricators, sail makers, and technicians.

The vessel’s silence also means it won’t harm right whales by polluting the ocean with underwater noise, which can have serious consequences for marine mammals. Noise pollution from ships disturbs these animals and interferes with their ability to communicate with other group members, offspring, and potential mates.

“At the heart of the work that the Song of the Whale team has always done, the central ethos is that we should develop and employ benign or noninvasive research techniques,” says McLanaghan.

In the late 1990s, McLanaghan and Song of the Whale collaborated with IFAW, the Bioacoustics Lab at Cornell University, and others to develop an automated detection system for maritime environments. The result is a system of buoys equipped with acoustic sensors that detect the sounds of whales nearby. One such system is currently deployed in the waters off New England and allows ships approaching the ports of Boston to be alerted and rerouted when right whales are present.

For this journey, McLanaghan and Song of the Whale have partnered with IFAW once again.

thermal sensing

On this journey north, the Song of the Whale plans a stop at Duke Marine Lab to pick up additional remote-sensing technology that will be especially useful at night: a thermal camera.

This specialised camera uses forward-looking infrared (FLIR) technology to create pictures from heat data. In the darkness of night, the thermal camera can locate spouts of water and air expelled by right whales and other cetaceans. Difficult to detect by eye at night, these “whale blows” are captured by the thermal camera because they register at a higher temperature than the surrounding air and water.

To accommodate the new equipment, the crew will build a custom mount high aloft the tall mast and outfit the research cabin with additional computing capabilities and wiring.

Knowing where right whales are is a key part of the puzzle in knowing how best to protect them.

This research will help fill critical gaps in our knowledge of the species. More than that, though, it will help us understand how to reduce the life-threatening risks these whales face every day, so we can pull them back from the brink of extinction once and for all.

Related content

Our work can’t get done without you. Please give what you can to help animals thrive.