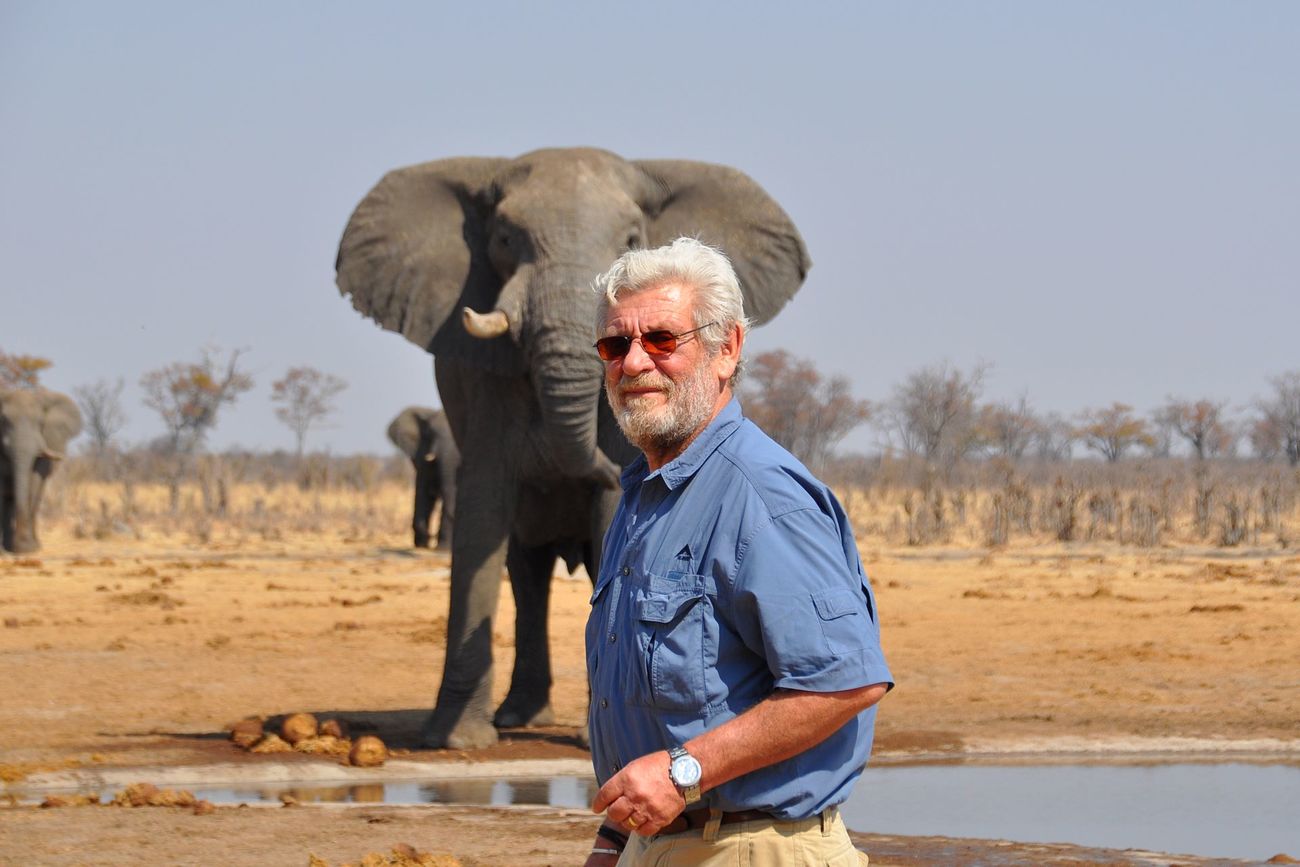

Jason Bell

Executive Vice President - Strategy, Programmes & Field Operations

If there's an individual animal in distress, why would you not make every effort to try and rescue it?

Room to Roam: the genesis of a game-changing vision for African conservation

‘Let them roam’ was the late Professor Rudi van Aarde’s mantra when questioned about African savannah elephants and their ability to survive into the future. ‘Give them enough space and freedom from human interference, and they will take care of themselves.’

Rudi’s unshakeable conviction that given such conditions, people and elephants can coexist and thrive is the essential distillation of his nearly 30-year journey exploring, through solid scientific investigation and understanding, the place of elephants in an increasingly dynamic and complex world. ‘This research matters,’ Rudi said, ‘because nature is the essence of life.’

As the head of the Conservation Ecology Research Unit (CERU) at the University of Pretoria, Rudi, with a small group of specialist scientists and technicians, was able to guide positive, science-based outcomes towards a future for elephants which, for many reasons, is far from secure.

CERU's efforts resonated strongly with IFAW's objectives for Africa's savannah elephants and their conservation, and for more than two decades, the organisation has not only supported the unit's research but has embraced it as the cornerstone of its Room to Roam initiative, which is one of the most visionary and important conservation initiatives of our time.’

The legacy that Rudi has left behind is immeasurable. We owe it to him to keep his legacy going and to ensure that elephants and people will thrive well into the future, and that science will continue to stand proud in its contribution to conservation management.

Key to the relevance and success of CERU’s work has been a thorough, critical review of conservation endeavours in Africa, both past and present.

Once, elephants thrived across Africa, but their numbers have declined from millions to about 400,000, mostly in and around national parks and other wildlife reserves. At the same time, Africa's human population continues to rise in urban and rural communities adjoining protected areas.

These wildlife havens are biodiversity strongholds, the ‘rooms’ where many of the continent’s iconic animals live. They are outstanding conservation achievements. Still, they continue to be threatened by rapid global land-use changes and human needs, a situation exacerbated by the now pervasive effects of climate change, not to mention the brutality of crime syndicates poaching for ivory, which drives elephant numbers into a downward spiral.

Furthermore, these parks and reserves don't exist as a single coherent unit; they are fragmented into nine identified clusters in the Southern African sub-region, some with stable elephant populations and others with declining numbers. Each cluster comprises core conservation areas, usually surrounded by buffer zones where people live and where wildlife is protected. Together, these core areas stretch over one-third of the protected land, accounting for at least half of the region's elephants, with the rest in the surrounding buffer areas. Still, it is concerning that at least 15 elephant populations in the sub-region are isolated from these clusters. Being cut off in this way impairs ecological processes and has unfortunate consequences for elephants and other species.

Elephant conservation certainly presents environmental challenges and a great deal of controversy. The highly polarising ‘elephant problem’ is a good example. Arguments are often framed around numbers—too few or too many—without a clear definition of an optimal population size.

Previously, wildlife managers in Southern Africa addressed overpopulation concerns through culling, believing it necessary to maintain ‘balance’ and ‘carrying capacity’. This approach led to the killing of thousands of elephants from the 1960s to the 1990s. However, culling failed to prevent vegetation damage, and elephant numbers rebounded once it ceased, proving that their impact was driven more by resource distribution than sheer population size. Therefore, instead of focusing on numbers, conservation should prioritise resilience by ensuring diverse habitats that support stable populations.

CERU's research led to a fundamental core conclusion—space. Elephants need space and lots of it to live without the uncertainties and consequences of human interference. For example, if habitat destruction is to be avoided, a population of 1,000 elephants needs an area of at least 2,500 square kilometers or more, depending on rainfall and where drinking water is found.

Given other human priorities, more land for elephants is unlikely. The alternative, therefore, is to optimise existing elephant landscapes. This can be achieved by linking small areas into functional units through corridors across human-dominated areas or by extending core areas onto surrounding buffer zones. Both options focus on connectivity, a nature-based solution that should improve the ability of elephant populations to withstand and recover from disturbances.

Elephant numbers fluctuate due to poor conservation practices, neglect, poaching, habitat loss, human-wildlife conflict, and climate-related phenomena like droughts and floods.

For example, while populations in West, Central, and North Africa decline through poor management, those in parts of East and Southern Africa are recovering due to conservation efforts.

The catch, though, is that although intense management practices, such as fencing and water provisioning, safeguard elephants from poaching and support their survival, they disrupt natural ecological processes by altering elephant movement and land use patterns. Preventing natural dispersal leads to isolated populations, turning parks into little more than ‘mega zoos’.

Connectivity, on the other hand, allows elephants to move freely and maintain ecological balance.

So, rather than focusing on historical wildlife numbers, conservation goals should consider available space and ecological dynamics. Connectivity is key to stabilising elephant populations while mitigating threats like poaching, inbreeding, and habitat loss. With a focus on anti-poaching initiatives, maintaining habitat integrity, and good governance, connectivity will ensure that elephants roam freely and persist across Africa, resilient to disturbances.

Connectivity thinking has promoted a new approach to elephant conservation—‘megaparks for metapopulations’. This strategy replaces outdated agricultural management approaches and mitigates human-made barriers such as country borders, fences, and agricultural expansion, which have fragmented elephant populations. It provides a powerful ecological platform for managing elephants and their impact, allowing for the dispersal of elephants according to the food and water at their disposal and the natural ebb and flow of their numbers.

IFAW's strong relationship with the CERU team and the development of their connectivity, megapark, and metapopulation concepts crystalised in 2018 when IFAW and Vivek Menon, advisor to IFAW and the founder and executive director of the Wildlife Trust of India, invited the CERU team to India to celebrate Gaj Mahotsav, a campaign and event dedicated to raising awareness of elephants in India, preventing human-elephant conflict, and protecting elephant corridors and habitats.

At this gathering, Rudi conceptualised how to fix conservation’s ‘broken plate’, a metaphor for the fragmented nature of protected areas across sub-Saharan Africa, and how we can try to reassemble the scattered shards using the principles defined in connectivity conservation, Rudi suggested using elephants to achieve this, as they are one of the widest-ranging species in Africa’s savannahs.

We will never be able to fully repair the broken plate. But with a foundation of good science and the committed support of governments, conservation partners, and communities, a functioning network of landscapes for elephants and people could be achieved.

Once back in Africa, IFAW organised a series of workshops with Rudi and his team at the Kapula Camp in Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park, a major stronghold for savannah elephants. Here, IFAW’s ‘Room to Roam’ vision was born.

Though still in its initial stage, IFAW is already working in several anchor areas strategically positioned for cross-regional connectivity. The broader ambition is to secure and connect 10 critical landscapes in East and Southern Africa, each home to at least 10,000 elephants. These anchor areas define their regions' most significant habitat fragments, all crucial to continuity across the savannah elephant’s range. The positive outcomes of this far-reaching initiative will be greater biodiversity, natural resilience to climate change, and a future where animals and people can coexist and thrive.

Jason Bell

Executive Vice President - Strategy, Programmes & Field Operations

If there's an individual animal in distress, why would you not make every effort to try and rescue it?

Every problem has a solution, every solution needs support.

The problems we face are urgent, complicated, and resistant to change. Real solutions demand creativity, hard work, and involvement from people like you.

Unfortunately, the browser you use is outdated and does not allow you to display the site correctly. Please install any of the modern browsers, for example:

Google Chrome Firefox Safari